Rival Systems Options Knowledge Base

Options For Beginners

- Select Your Level

- Beginner

- Intermediate

- Advanced

The Basics of Options

Welcome to the dynamic world of options trading!

Whether you're a seasoned investor looking to diversify your portfolio or a newcomer eager to explore new investment opportunities, options trading has something for everyone.

Beginners Guide to Options is a series on options trading that assumes no prior knowledge or experience. It provides an excellent foundation for moving on to the other two courses, Intermediate Guide to Options and Advanced Guide to Options.

Options trading may initially seem complex, but success depends on disciplined learning, careful risk management, and ongoing practice. We have kept theoretical discussions to a minimum, and no advanced mathematics is required. This is not meant to discourage traders interested in options theory and comfortable with higher mathematics from seeking a more detailed discussion of option theory from more advanced courses. The emphasis in this beginner series is on the practical aspects of options trading.

Since each chapter builds on the material in previous chapters, we strongly urge new traders to resist the temptation to skip to a new chapter without fully mastering the material in the preceding chapters. By covering the material step by step in an orderly fashion, new traders will find that each chapter becomes the foundation for each subsequent chapter and, consequently, a solid foundation on which to build a successful trading career.

Disclaimer

The material in this options guide is meant for educational purposes only. The information, strategies, and examples presented are not to be construed as trading or investment advice. Rival Systems does not endorse or recommend specific trading or investment decisions and users are encouraged to exercise their own judgement and seek professional advice before making any financial decisions.

Users are urged to carefully consider their financial objective, risk tolerance, and level of experience before engaging in trading or investment activities. Rival Systems is not responsible for any inaccuracies, errors, or omissions in the educational content or for any actions taken in reliance on such content.

What Are Options?

Options are a type of financial instrument that allows the buyer to choose whether to purchase or sell an underlying asset at a predetermined price within a specified timeframe.

These instruments allow for flexibility, enabling investors to benefit from rising and falling markets. Every option market brings together many different market participants, each searching for the best way to achieve their own unique goals. A participant may be motivated to profit from an expected directional move in the market or price disparities between similar or related products.

Or they may be motivated by a desire to reduce the risk of some pre-existing position. And some market participants act as middlemen, buying and selling as an accommodation to others and hoping to profit from the difference between the bid and ask price.

Whatever a participant's goals, it's only possible to achieve them through clear communication with other market participants and an intrinsic understanding of a trader's rights and responsibilities when the trader enters an options market contract.

For this reason, every option trader's education must begin with the basics: an introduction to options trading terminology and the rules and regulations governing the trading activity. Otherwise, a trader will be unprepared for the real risks of trading and unable to make the best use of options to reach their goals.

Contract Specifications

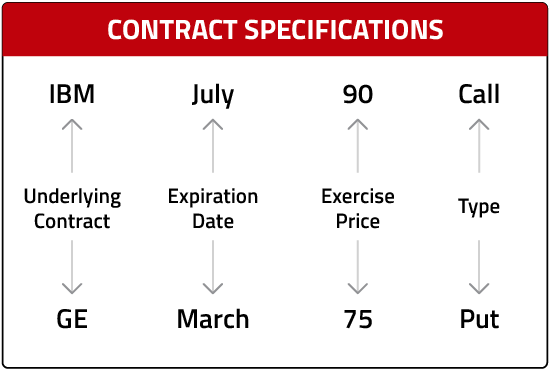

We begin with the specifications of an option contract, the terms a trader must be familiar with to enter and succeed in an options market. The basic contract specifications are shown below.

Calls and Puts

Options come in two types.

Call Option

A call option is the right to buy or take a long position in a given asset (typically a security, commodity, index, or futures contract) at a fixed price on or before a specified date.

Put Option

A put option is the right to sell or take a short position in a given asset. Before going further, two terms are widely used among traders but need clarification. The terms long and short can take on several different meanings, but the most common interpretations and the ones generally followed in this program, are as follows:

- A long position results from the purchase of a contract or strategy

- A short position results from the sale of a contract or strategy

Position

A position is the total of a trader's open contracts in a particular underlying market. Because a long position results from a purchase, it usually requires an outlay of cash or a debit to the trader's account. Because a short position is the result of a sale, it usually results in cash being received or credited to the trader's account.

Understanding Underlying Contracts and Exercise Price

The asset to be bought or sold under the terms of an option is the underlying asset or contract, or, more simply, the underlying. The most common underlying contracts for exchange-traded options are stocks, foreign currencies, and futures contracts.

|

Stocks |

Foreign Currency |

Futures Contracts |

Each exchange determines the amount of the underlying asset controlled by an option contract. For exchange-traded stock options, the number of shares comprising the underlying contract may differ from exchange to exchange but is usually 100 shares.

The exercise price, or strike price, is the price at which the underlying will be delivered should the holder of an option choose to take advantage of their right to buy or sell.

While the amount of the underlying contract and the exercise price are determined by the exchange, it is possible under some conditions for these specifications to change. For example, in the event of stock splits or special dividends, an exchange may adjust the number of underlying shares and the exercise price to reflect the adjusted value of the stock.

If a stock is split 2 for 1, a 100 call will become a 50 call, with the right to buy 200 shares of stock. Whether a trader buys 100 shares for $100 per share or 200 shares for $50 per share, the cost is $10,000. Such adjustments are therefore considered accounting changes and do not materially affect an option’s value.

Check Out Rival One Options Functionality

Option Expiration Dates

The date after which the rights associated with the option cease to exist is the expiration date or expiry. The expiration date, like other contract specifications, is determined by each exchange. Exchanges have recently started listing options more frequently so there is usually an option expiring every day of the week.

The expiration date for options on futures may vary from one exchange to another, but sometimes occurs in the month prior to the expiration month designated in the contract. A March option can expire sometime in February; a September option can expire sometime in August. The exact expiration date can only be determined by consulting an exchange calendar.

Zero Days To Expiration Options (ODTE)

Historically traders would buy or sell an option months before it was set to expire. As the exchanges started listing weekly options that result in an option expiration every day of the week, more traders have started waiting to trade the option on the day it is set to expire. The term ODTE options refers to the trading an option on the day it expires. On expiration day the option has “zero days to expiration”.

Options Rights and Obligations

Note that in option trading, all rights lie with the buyer and all obligations with the seller.

| Rights | Obligations |

|---|---|

| Options Buyer | Options Seller |

|

The buyer of an option may choose to:

The choice is solely theirs. The buyer's only obligation is to pay the agreed-upon price for the option. |

In contrast, the actions of the buyer determine the seller's obligations.

|

Fundamentals of Settlement Procedures and Types

Depending on the exchange and the type of underlying contract, options may be subject to either stock-type settlement or futures-type settlement.

| Stock-Type Settlement |

|---|

|

The stock-type settlement requires full cash payment for the contract when a trade is made. If options are subject to stock-type settlement and a trader buys an option for 2.00, with each point having a value of $1,000, the trader must pay the seller of the option $2,000 in cash. The trader who buys the option will lose the use of the money (they will not be able to earn any interest), while the trader who sells the option will earn interest on the cash received. Moreover, all profits or losses are unrealized until the position is closed out. If the option's price rises from 2.00 to 3.00, the trader will profit $1,000. But this profit only appears on paper, and the trader will only have access to the funds once they go into the marketplace and sell the option to someone else. |

| Futures-Type Settlement |

|---|

|

In a futures-type settlement, no cash initially passes from the buyer to the seller. Each side must deposit some amount of margin money which guarantees that both parties will fulfill any future financial obligations resulting from the trade. Each day there is a cash settlement based on the change in the contract's price in the marketplace. If the contract rises in value, the buyer receives a payment from the seller equal to the change in the contract's price. If the contract falls in value, the seller receives a payment from the buyer. This daily variation payment occurs even if the position is not closed out. In theory, there is no loss of interest associated with a margin deposit since margin money is assumed to belong to the trader, even though the funds may reside in an account at a clearing organization. Since the margin money belongs to the trader, any interest accrues to the margin deposit also belongs to the trader. However, this is true only in theory. Many brokerage firms retain the interest earned on margin deposits rather than returning it to the customer. |

Logically, options should be subject to the same settlement procedure as the underlying contract. If the underlying contract is subject to stock-type settlement, then the options on that contract should be subject to stock-type settlement.

If the underlying contract is subject to futures-type settlement, the options should be subject to futures-type settlement. This is indeed the case in stock options markets. However, this is only sometimes true in futures options markets.

Exchange-traded options on futures contracts in the United States are typically subject to stock-type settlement. In contrast, options on futures in Europe and typically subject to futures-type settlement. When options on futures are subject to stock-type settlement, trading can be significantly more cash intensive than if the options are subject to futures-type settlement.

A trader should always check with the exchange to determine the applicable settlement procedure, whether stock-type or futures-type.

Check Out Rival One Options Functionality

The Difference Between a Long and Short Option Position

Before going further, the terms long and short are widely used among traders but the terms can mean different things when it comes to general trading versus options.

| General Meaning of a Long Market Position | Generel Meaning of a Short Market Position |

|---|---|

|

Typically, a long market position is one in which an upward move in the price of the underlying market will increase the value of the position. |

A short market position is one in which a downward move in the price of the underlying market will increase the value of the position. |

Options Long and Short Positions

But in option trading the terms long and short usually refer to the purchase or sale of a contract.

| Options Long Market Position | Options Short Market Position |

|---|---|

|

A long position results from the purchase of a contract or strategy. Because a long position is the result of a purchase, it usually requires an outlay of cash, or a debit to the trader's account. |

A short position results from the sale of a contract or strategy. Because a short position is the result of a sale, it usually results in cash being received, or a credit to the trader's account. |

As we will see, it is possible to have a long option position (a position where the trader has purchased an option) and at the same time have a short market position (a position where the trader wants the price of the underlying to decline).

In the same way, it is possible to have a short option position (a position where the trader has sold an option) and at the same time have a long market position (a position where the trader wants the price of the underlying to rise).

Chapter 02

Premium Components

Premium Components

An option's price, or premium, is determined by supply and demand. This is typical of all competitive markets. Buyers and sellers make competing bids and offers: when a bid and offer coincide, a trade is made.

Premium

The price of an option.

While an option's price is always quoted as one number in the marketplace, it is often useful when discussing option characteristics to break the price into several components. These components in turn depend on the relationship of the option's exercise price to the price of the underlying contract.

Intrinsic Value and Time Value

The premium paid for an option can be separated into two components: Intrinsic Value and Time Value. An option's price, or premium, is always made up of its intrinsic value and its time value.

| Intrinsic Value | Time Value |

|---|---|

|

An option's intrinsic value is the amount which would be credited to the option holder's account if they were to exercise the option and close out the position against the underlying contract at the current market price. For example, with an underlying ABC contract trading at 110.00, the intrinsic value of an ABC October 100 call is 10.00. |

The amount of intrinsic value is the amount by which the price of an underlying contract exceeds a call's exercise price or the amount by which a put's exercise price exceeds the price of the current underlying contract. No option can have an intrinsic value less than zero. If an option's price is greater than its intrinsic value, the additional amount is the option's time value. |

By exercising their option, the holder of the 100 call can buy the ABC contract for 100. If they sell the contract at the market price of 110.00, the result will be a 10.00-point credit to their account.

With an underlying XYZ contract trading at 76.00, the intrinsic value of an XYZ March 80 put is 4.00. The put holder can sell the XYZ contract at 80 by exercising their option. If they repurchase the contract at the market price of 76, the result will be a credit of 4.00 points.

No Option Can Have an Intrinsic Value of Less than Zero

-

Calls

A call will only have intrinsic value if its exercise price is less than the current market price of the underlying contract. -

Puts

A put will only have intrinsic value if its exercise price exceeds the underlying contract's current market price.

The amount of intrinsic value is the amount by which the call's exercise price is less than the current underlying price or the amount by which the put's exercise price is greater than the current underlying price.

Most options in the marketplace trade at a price greater than intrinsic value. The additional amount of premium beyond the intrinsic value which traders are willing to pay for an option is the time value or time premium. Market participants are often willing to pay this additional amount because of the protective characteristics afforded by an option over an outright long or short position in the underlying contract.

An option's price is always composed of its intrinsic value and time value. If an ABC October 100 call is trading at 15.00 with the underlying ABC contract at 110.00, the time value of the call must be 5.00 since the intrinsic value is 10.00.

The two components must add up to the option's total price of 15.00. If an XYZ March 80 put is trading for 9.00 with the underlying XYZ contract at 72.00, the time value of the put must be 1.00 since the intrinsic value is 8.00. The intrinsic and time values must add up to the option's premium of 9.00.

Even though an option's premium is always composed of its intrinsic and time values, one or both can be zero. If the option has no intrinsic value, its price in the marketplace will consist solely of time value. If the option has no time value, its price will consist exclusively of intrinsic value. In the latter case, traders often say the option is trading at parity. At expiration, an option's time value is always zero.

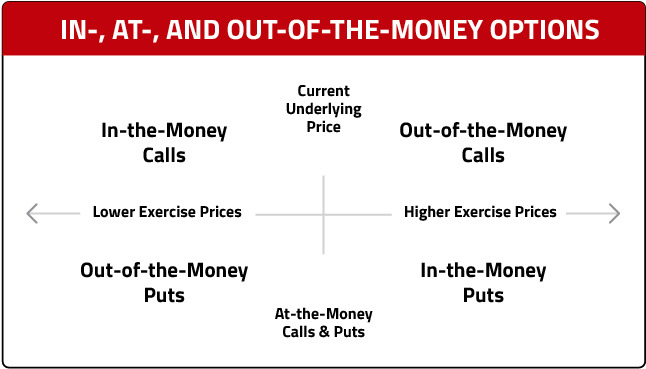

In-, At-, or Out of the Money Options

If an option has some amount of intrinsic value, it is said to be in-the-money by an amount equal to its intrinsic value. With a stock at 44, a 40 call is 4 in-the-money. With a stock at 91, a 100 put is 9 in-the-money. If an option has no intrinsic value, it is said to be out-of-the-money.

The price of an out-of-the-money option consists solely of time value. A call (put) will be in-the-money if its exercise price is lower (higher) than the current price of the underlying contract. If a call is in-the-money, a put with the same exercise price and underlying contract must be out-of-the-money. Conversely, if the put is in-the-money, a call with the same exercise price must be out-of-the-money.

| |

In-the-money An option which could be exercised and immediately closed out against the underlying contract for a cash credit. A call is in-the-money if its exercise price is lower than the current market price of the underlying. A put is in-the-money if its exercise price is higher than the current market price of the underlying. |

|

|

Out-of-the-money An option which currently has no intrinsic value. A call is out-of-the-money if its exercise price is higher than the current market price of the underlying. A put is out-of-the-money if its exercise price is lower than the current price of the underlying. Occasionally an option's exercise price will be exactly equal to the current price of the underlying contract. When this happens, the option is said to be at-the-money. Technically, such an option is also out-of-the-money since it has no intrinsic value. The distinction between an at-the-money and out-of-the-money option is often made because an at-the-money option has the greatest amount of time premium and is usually traded very actively. |

|

|

At-the-money An option whose exercise price is equal to the current price of the underlying contract. On listed option exchanges the term is more commonly used to refer to the option whose exercise price is closest to the current price of the underlying contract. In theory, for an option to be at-the-money its exercise price must be identical to the current price of the underlying contract. However, for exchange-traded options the term is commonly applied to the call and put whose exercise price is closest to the current price of the underlying contract. With a stock at 74 and 5 between exercise prices (65, 70, 75, 80, etc.), the 75 call and the 75 put would be considered the at-the-money options. These are the call and put options with exercise prices closest to the current price of the underlying contract. |

Chapter 03

Excercising an Option

Exercising an Option

An option carries with it the right to convert the option into either a long or short position in the underlying contract. The process by which this is accomplished, and any restrictions on this process, are important considerations for an option trader.

Exercise and Assignment

The holder of a call or a put option has the right to exercise the option prior to its expiration, thereby converting the option into a long underlying position, in the case of a call option, or a short underlying position, in the case of a put option. A trader who exercises an ABC October 100 call has chosen to buy 100 shares of ABC stock at 100 per share. A trader who exercises an XYZ March 80 put has chosen to sell 100 shares of XYZ stock at 80 per share. Once an option is exercised it ceases to exist, just as if it had been allowed to expire unexercised.

Exercise

The process by which the holder of an option notifies the seller of their intention to take delivery of the underlying contract in the case of a call, or to make delivery of the underlying contract in the case of a put, at the specified exercise price.

Assignment

The process by which the seller of an option is notified of the buyer's intention to exercise.

A trader who intends to exercise an option must submit an exercise notice to the seller of the option, if purchased from a dealer, or to the exchange on which the option was purchased. When a valid exercise notice is submitted, the seller of the option will be assigned. Depending on the type of option, they will be required to take either a long or short position in the underlying contract at the specified exercise price.

To avoid confusion, many exchanges will exercise in-the-money options at expiration for the holder of the option, regardless of whether the holder submits an exercise notice. This is referred to as automatic exercise. If the holder of an option wants to let an in-the-money option expire unexercised, or if they want to exercise an out-of-the-money option, they must submit their request to the exchange.

Automatic Exercise

The process by which the seller of an option is notified of the buyer's intention to exercise.

American and European Options

Most options fall into two exercise categories: European and American. A European option can be exercised only at expiration, while an American option can be exercised any time prior to expiration.

American Option

An option which can be exercised at any time prior to expiration.

European Option

An option which can only be exercised at expiration.

Flex Options

In an effort to compete with activity in over-the-counter option trading, exchanges have introduced flex options. The contract specifications of flex options need not match those of standardized exchange-traded options but can be negotiated between the buyer and the seller at the time the option is traded.

The negotiated specifications include the exercise price, expiration date, and exercise procedure (European or American). As with all exchange traded options, the exchange clearing house guarantees the integrity of a trade in a flex option.

|

Market Structure |

Exchanges serve as platforms where buyers and sellers of assets can connect for trading. Originally established for face-to-face negotiations, exchanges have evolved into open-outcry and electronic markets. In open-outcry markets, traders verbally or through hand signals announce bids and offers, facilitating transparency but risking miscommunication. Electronic markets automatically match buyers and sellers. Over-the-counter (OTC) transactions occur outside exchanges, allowing direct negotiation but bearing counterparty risk and potential for less favorable pricing. |

|

Making a Trade |

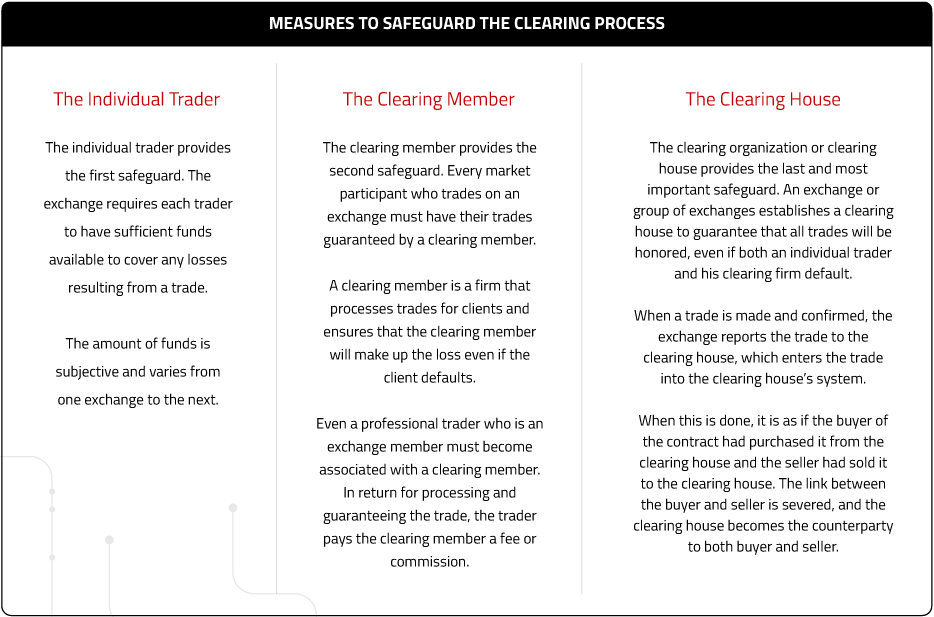

Exchanges ensure trading confidence through a series of safeguards. Traders must have sufficient funds to cover potential losses. Clearing members guarantee trades and are responsible for defaults, charging fees in return. The critical safeguard is the clearing house, a part of the exchange or a separate entity, guaranteeing trade fulfillment even if both trader and clearing member default. |

|

Basic Options Strategies |

Understanding options strategies is essential for profitable trading. Option values at expiration depend solely on the underlying contract's price. Profits or losses are determined by comparing the initial trade price and expiration value. Simple strategies include long and short positions featuring various profit and loss outcomes. |

|

Combination Strategies |

Combining options offers complex strategies for traders beyond basic buying and selling. Using expiration profit and loss diagrams based on underlying stock prices helps visualize outcomes. Rules for understanding these diagrams include straight lines, bends at exercise prices, and in/out-of-the-money behavior. Examples show various scenarios: buying both a call and put, selling both, and selling at different exercise prices. These combinations have unique risk-reward profiles, and traders can create diverse positions to navigate market conditions effectively. |

|

Hedging Strategies |

Options serve as hedges against underlying asset positions, but hedging comes with costs, which could be premium payments, lost opportunities, or additional risks. Hedging decisions depend on balancing potential losses and gains. Protective options, like puts and calls, offer downside or upside protection respectively, at the cost of the premium paid. Covered options involve selling options against underlying positions: covered calls offer limited downside protection, covered puts offer limited upside protection. Combining protective and covered options creates complex strategies known as fences, collars, or range forwards. Long fences/collars combine protective puts with covered calls, offering limited downside and upside, while short fences/collars involve protective calls with covered puts, limiting upside and downside. These strategies can be balanced to offset premiums, creating a zero-cost collar. |

|

Order Types |

Understanding the intricacies of submitting orders to buy or sell contracts on exchanges is crucial for optimizing options trading opportunities. Different order types and their execution on exchanges are pivotal to grasping effective options trading. Exchange-imposed trading restrictions could impact order execution as well. To avoid unexpected heightened risks, traders must comprehend these limitations. |

Chapter 04

Market Structure

Options Market Structure

How can someone desiring to buy an asset find a potential seller? How can someone wishing to sell an asset find a potential buyer? To facilitate trading, exchanges have been established whereby buyers and sellers can connect to transact business conveniently.

Exchanges also guarantee the integrity of the marketplace by ensuring that each party will fulfill all obligations resulting from a trade. If a dispute arises regarding the terms of a transaction, the exchange will have rules and regulations by which the dispute can be equitably resolved.

Specialists and Market-Makers

Even if someone desiring to buy or sell an asset goes to a recognized exchange, how can they be sure that some other exchange member will want to take the other side of the trade?

Perhaps every potential counterparty is on vacation.

To maintain credibility, exchanges must ensure that there will always be a buyer when someone wants to sell and a seller when someone wants to buy. To achieve this, an exchange may appoint a specialist for each exchange-traded contract or group of contracts. A specialist is an individual or trading firm prepared to risk its own capital by making a continuous market in a specific contract.

Whenever a buyer or seller enters the market for a given contract, the specialist will quote a price at which they are willing to buy and a price at which they are willing to sell the contract. There may be better bids or offers in the market than those made by the specialist, and a potential customer will always be able to make a trade at the best price.

But a customer can always be sure that at least one buyer or seller will be available in the form of a specialist. In return for guaranteeing a market in their appointed contract, a specialist is given priority when their market matches the market of other buyers or sellers. In addition to acting as a principal, the specialist may also profit by acting as an agent, matching buy and sell orders even when they do not participate in the trade.

Competing Pool System

Some markets, rather than being organized on a specialist system, consist of a pool of competing market-makers. Like a specialist, a market-maker is willing to risk their own capital by continuously making bids and offers in each market. The primary difference between a specialist and market-maker systems is that all market-makers are equal and compete with all other market participants for orders.

Moreover, a market-maker may trade only for their own account. If a market-maker is present in a market, when requested, they must quote a price at which they are prepared to buy and a price at which they are prepared to sell. However, while a specialist is always required to make a market, a market-maker is not obligated to be present at all times.

If there are unlikely enough market-makers in a given market to ensure liquidity, an options exchange may appoint a designated primary market-maker (DPM) or a lead market-maker (LMM). DPMs and LMMs perform the same functions as a specialist, except that an LMM can act only as a principal, buying and selling for their own account, rather than as both principal and agent.

Market Participants

We have already looked at some of the full-time professionals who trade for their own account in a market: specialists, market-makers, and locals. But professional traders are not the only participants in a market. There are many different reasons why an institution or an individual might want to enter a marketplace, and there are many different trading strategies that can be pursued.

Derivative exchanges were initially established to enable the holder of a position in an underlying asset to hedge away some or all of the risk associated with the position. While there may be other reasons to enter a derivative market, hedgers still comprise a large segment of the market population. Often the underlying position which needs to be hedged is the result of an active investment decision, such as an investment in a stock or commodity. If the investor wants to reduce the position's size temporarily, they can hedge away some of the risks by using the derivative market.

Sometimes, however, the underlying position is simply the result of normal commercial activity. For example, a manufacturer who borrows money at a floating rate to invest in new production equipment has a short interest rate position. They want interest rates to decline, not because they have invested in the interest rate market, but because lower interest rates will reduce their borrowing costs. Suppose someone believes the risk of holding a position in an underlying asset is too significant. He can reduce this risk by entering a derivative market and taking an appropriate hedge position.

In contrast to a hedger, a speculator may have a definite opinion about how the price of some asset will move. Instead of taking a position in the actual asset, they may find that a derivative market offers a more convenient way to take a position. After all, an investor who believes that grain prices will rise may find it impractical to buy grain and store it until the price does rise. However, the investor can buy a futures contract and, if they are correct, profit from the same expected price increase.

Still, other traders may decide based on a perceived price relationship between different assets. If the relationship appears to be mispriced in the marketplace, the trader can execute a spread by selling the asset which seems overpriced and buying the asset which appears underpriced. The spreader expects to profit when the price relationship returns to its expected value.

Chapter 05

The Trading Process

Options Trading for Beginners; Exchange & Clearing

As a valuable tool to diversify investments, generate income streams, or understand the complexities of the financial market, anyone can learn to trade options, not just financial experts or options traders. Here, we will explore the basic architecture of how option orders work through the instruments of exchanges and clearing firms.

Most market participants are interested primarily in the prices at which they can execute a trade. But the prices are determined by a variety of market forces. To fully understand the forces at work in the marketplace and make the most of an options trading strategy, it will be helpful to understand what happens when an option trade is made.

How does the order to buy or sell a contract reach the marketplace?

Making a Trade

A professional trader who is an exchange member only needs to announce their bid or offer in the marketplace, whether open-outcry or electronic, and see if a counterparty is available. If so, the parties will agree on price and quantity terms and confirm the trade.

A retail or institutional investor who is not an exchange member but wants to make a trade must find a member willing to act as a broker and execute the trade on the investor’s behalf. This is usually not difficult since many brokerage firms become members of an exchange to execute orders for their clients.

There are, of course, fees whenever an order is executed. A brokerage firm must pay a fee to a floor broker who executes an order. The client will have to pay a fee to the brokerage firm. And every trade made on an exchange requires payment of a fee to the exchange. Each party must pay this fee to a trade and, in the case of a retail or institutional client, it will be passed on to the client by the member firm. However, the landscape of brokerage fees has changed with the advent of payment for order flow (PFOF). This practice involves brokerage firms receiving compensation for directing orders to particular market makers or trading venues. This compensation can be in the form of monetary payments or other benefits. As a result, many brokers have been able to reduce their trading fees to zero for their clients.

The Clearing Process

Anyone who makes a trade wants to be confident that the counterparty to the trade will fulfill any obligation resulting from the trade. What would be the point of trading if one could not be sure that the terms of a trade would be honored? To engender confidence and maintain credibility, exchanges have established a series of safeguards that ensure that all trades will be honored.

A clearing house may be established to guarantee the trades on one specific exchange. Or a clearing house may be established to ensure trades on several different exchanges, such as the Options Clearing Corp., which guarantees transactions on all stock option exchanges in the United States.

A clearing house must always maintain sufficient reserves to meet whatever financial obligations may arise. As a result, market participants can be confident that any trade made on an exchange will be honored.

Margin Requirements

When the clearing house severs the link between buyer and seller, two new connections are established: between buyer and clearing house and between seller and clearing house. These new links mean that the clearing house now takes on the responsibility of guaranteeing that the terms of the trade are fulfilled.

If the original trade involves a security, such as a stock or bond, the clearing house will fulfill its obligations by collecting the required funds from the buyer and transferring them to the seller. At the same time, it will obtain the security from the seller and transfer it to the buyer. Once this is done, the clearing house has fulfilled its responsibilities.

If, however, the terms of the contract call for some future financial transaction, such as the fulfillment of a futures contract, the clearing house will initially collect a margin deposit from both the buyer and the seller. This acts as a bond against future financial obligations. As market conditions change, the risk for one party or the other may increase.

When this happens, the clearing house usually collects additional money commensurate with the increased risk to protect itself against a possible default.

A clearing house must carefully consider the level at which it sets margin requirements. While margin requirements must be set high enough to protect the clearing house against the risk of default, they must not be set so high as to stifle trading.

In addition to margin requirements, a professional trader on a securities exchange may also be subject to a haircut requirement. This is a capital amount that the trader is required to maintain based on the value of securities in their account. In the United States, haircut requirements are usually set by the Securities Exchange Commission.

The Exercise and Assignment Process

The clearinghouse is also responsible for processing exercise and assignment notices for options. A trader desiring to exercise an option must submit a valid exercise notice to their clearing firm, which forwards it to the clearing house. The clearinghouse then randomly chooses from all open options identical to the one specified in the exercise notice. The seller of the selected option will then be informed by their clearing firm that they have been assigned.

The exercise and assignment process requires one party to take a long position in the underlying asset and one party to take a short position in the underlying asset at the specified exercise price. The clearinghouse accomplishes this by collecting the required funds from the party taking the long position and transferring them to the party taking the short position.

At the same time, the clearing house will transfer the underlying asset in the opposite direction. The transfer may be done through each trader’s clearing firm, but the clearinghouse is ultimately responsible for completing all transactions.

Once the exercise and assignment process has been completed, the clearing house has no further obligation since the option contract ceases to exist.

Chapter 06

Basic Strategies

Basic Options Trading Strategies: A Beginners Guide

Welcome to our comprehensive guide on options trading strategies for beginners. Options trading presents a wealth of opportunities for those who utilize specific strategies to minimize risk and maximize profits. Our goal is to help you understand and implement these strategies, so you can confidently begin your options trading journey.

We'll start by explaining the basics of options trading and then delve into a variety of strategies. We'll provide guidance on how to apply these strategies in real-world scenarios.

Options Strategies

To become familiar with some of the fundamental characteristics of options contracts, looking at some simple strategies will be helpful.

The choice of any strategy depends on whether it is likely to be profitable and therefore generates income. This, in turn, depends on the original trade price and the price at which the strategy is liquidated.

While no one can know for sure what the price of an option will be at some later date, we know that at expiration, an option's value depends solely on the price of the underlying contract.

- The option is worth zero if it is either at-the-money or out-of-the-money.

- Or it is worth intrinsic value (parity) if it is in-the-money.

Consequently, if an option position is held to expiration date, the profitability of the position is simply a function of the price of the underlying contract.

Purchasing an option will be profitable if its trade price is less than its value at expiration. The sale of an option will be profitable if its trade price is greater than its value at expiration.

Because the value of an option position at expiration depends solely on the price of the underlying contract, we can construct a graph of the value of any option position at expiration. While it is true that very few option positions are initiated and held to expiration, such charts can still help a new trader understand some of the primary risk/reward characteristics of either simple option purchase or sale strategies or of more complex combination positions.

Since all option strategies are combinations of individual contracts, the easiest way to become familiar with expiration values is to look at the value of an individual contract.

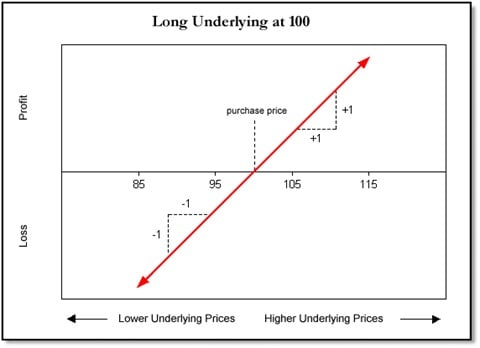

Buying and Selling the Underlying Contract

If a trader purchases an underlying contract and holds it for some time, the profit or loss at the end of the holding period is simply a function of the underlying price at that time.

- For each point the underlying contract rises above the purchase price, the trader will realize a profit of one point.

- For each point the underlying contract falls below the purchase price, the trader will realize a loss of one point.

A simple one-to-one correlation exists between movement in the futures price and the resulting profit or loss. This is shown in the following graph, where a trader purchases an underlying contract at 100.

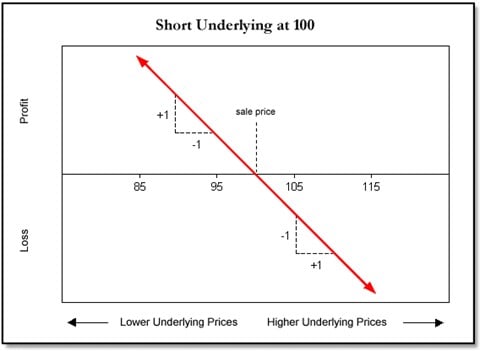

If a trader sells an underlying contract, the situation is just reversed. For each point the underlying contract falls below the purchase price, the trader will realize a profit of one point. For each point the underlying contract rises above the purchase price, the trader will realize a loss of one point.

There is still a one-to-one correlation between underlying price movement and the resulting profit or loss, but now the correlation is inverted. This is shown in the following graph, where a trader sells an underlying contract at 100.

In addition, whether one buys or sells an underlying contract, the potential risk and reward are unlimited. If the underlying price moves in the trader's favor or against him, there is no limit to the profit or loss.

Indeed, most underlying contracts cannot drop below zero in price, so the downside profit or loss is theoretically limited. But in practice, most traders consider an outright underlying position, whether long or short, as open-ended.

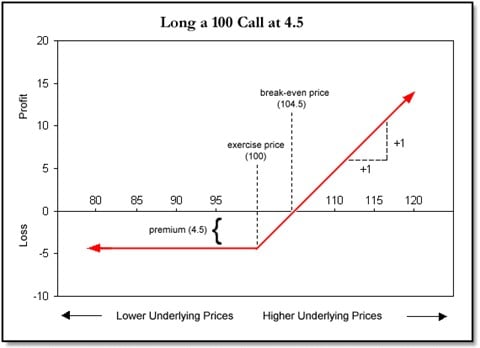

Buying a Call

The profit or loss at expiration resulting from a long call position is shown in the following graph.

The call is worthless below the exercise price of 100, so the position will show a loss equal to the amount paid for the call. Above the exercise price, the call takes on the characteristics of a long underlying position, gaining one point in value for each point the underlying rises in value.

The underlying price at which the purchase of the call will break even is equal to the exercise price plus the premium paid for the call. A trader who buys a 100 call for 4.50 will show a loss of 4.50 if the underlying is anywhere below 100 at expiration.

Above 100, the call will gain one point in value for each point the underlying price exceeds 100. The breakeven price on the long call position is 100 (the exercise price) plus 4.50 (the premium paid), or 104.50.

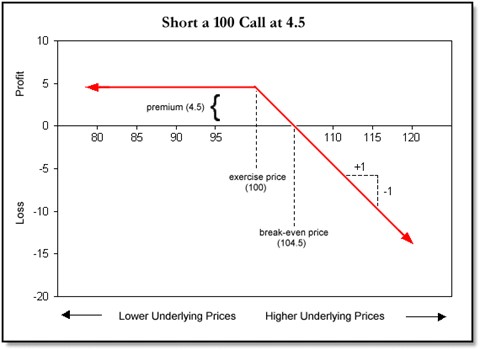

Selling a Call

The profit or loss at expiration resulting from a short call position is shown in the following graph.

Below the exercise price, the call is worthless, so the position will show a profit equal to the amount received for the call. Above the exercise price, the call takes on the characteristics of a short underlying position, losing one point in value for each point the underlying rises. The underlying price at which the sale of the call will break even is the exercise price plus the premium paid for the call.

A trader selling a 100 call for 4.50 will show a maximum profit of 4.50 if the underlying is below 100 at expiration. Above 100, the call will lose one point in value for each point the underlying price exceeds 100. The break-even price on the short-call position is 100 (the exercise price) plus 4.50 (the premium paid), or 104.50.

Buying a Put

The profit or loss at expiration resulting from a long-put position is shown in the following graph.

Above the exercise price, the put is worthless, so the position will show a loss equal to the amount paid for the put. Below the exercise price, the put takes on the characteristics of a short underlying position, gaining one point in value for each point the underlying falls. The underlying price at which the purchase of the put will break even is the exercise price less the premium paid for the put.

A trader buying a 100 put for 3.25 will show a loss of 3.25 if the underlying is above 100 at expiration. Below 100, the put will gain one point in value for each point the underlying price falls below 100. The break-even price on the long-put position is 100 (the exercise price) less 3.25 (the premium paid), or 96.75.

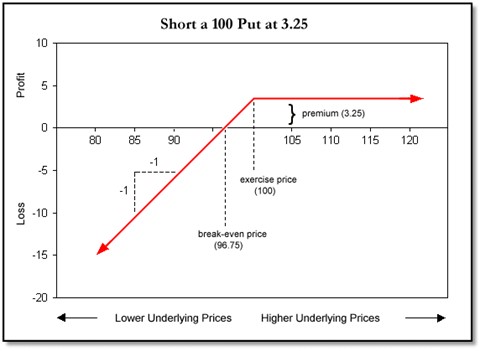

Selling a Put

The profit or loss at expiration resulting from a short put position is shown in the following graph.

Above the exercise price, the put is worthless, so the position will show a profit equal to the amount received for the put. Below the exercise price, the put takes on the characteristics of a long underlying position, losing one point in value for each point the underlying falls. The underlying price at which the sale of the put will break even is the exercise price less the premium paid for the put.

A trader selling a 100 put for 3.25 will show a maximum profit of 3.25 if the underlying is above 100 at expiration. Below 100, the put will lose one point in value for each point the underlying price falls below 100. The break-even price on the short put position is 100 position (the exercise price) less 3.25 (the premium paid), or 96.75.

The Risk-Reward Characteristics of Simple Positions

All the preceding graphs bend at the exercise price because an option can never have a value less than zero. If, at expiration, the underlying is below the exercise price in the case of a call or above the exercise price in the case of a put, the option's value goes to zero, but no lower.

The maximum loss (profit) for the buyer (seller) of an option is the option's premium. This leads to one of the most important characteristics of options: The buyer of an option has limited risk and unlimited reward; the seller of an option has limited reward and unlimited risk. We can summarize the risk/reward characteristics of the basic positions as follows:

| Position | Upside Risk-Reward | Downside Risk-Reward |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 07

Combination Strategies

Option Combination Strategies: Buying and Selling

Aside from basic buying and selling tactics, combining option strategies is also a viable technique for hedging. Similar to simple positions, we can create a profit and loss diagram with an expiration date solely based on the underlying stock's price.

While a new trader may find expiration profit and loss graphs challenging to visualize, several simple rules governing such graphs may help:

- All expiration graphs combine straight lines; there are no curves.

- If a graph bends, it will always do so at an exercise price; graphs never bend between exercise prices.

- A long (short) call in-the-money acts like a long (short) underlying position; an out-of-the-money call acts like zero.

- A long (short) put, which is in-the-money, acts like a short (long) underlying position; an out-of-the-money call acts like zero.

Buying a Call and Buying a Put

Suppose a trader buys a May 100 call for 4.50 and a May 100 put for 3.25. The expiration profit and loss diagram looks as follows:

At May expiration, if the stock finishes at 100, both the May 100 call and the May 100 put will be worthless, and the trader will lose their total investment of 7.75.

If the stock is above 100 >>, the put will be worthless, but the call will go into-the-money and take on the characteristics of a long stock position, gaining one point in value for each point the stock rises.

If the stock is below 100 >>, the call will be worthless, but the put will go into-the-money and will take on the characteristics of a short stock position, gaining one point in value for each point the stock falls.

For the position to break even, either the call or the put must be worth 7.75. This will happen if the stock is at 107.75 or at 92.25. Above 107.75 and below 92.25, the potential profit to the position is unlimited.

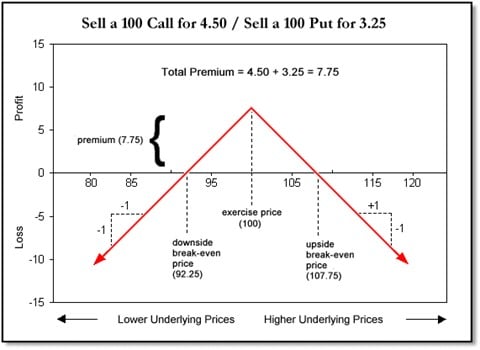

Selling a Call and Selling a Put

Suppose a trader sells a May 100 call for 4.50 and sells a May 100 put for 3.25. The expiration profit and loss diagram looks as follows:

At May expiration, if the underlying contract finishes right at 100, both the May 100 call and the May 100 put will be worthless, and the trader will get to keep the total premium of 7.75.

If the underlying contract is above 100>>, the put will be worthless, but the call will go into-the-money. It will take on the characteristics of a short underlying position, resulting in a loss of one point for each point the underlying price rises.

If the underlying contract is below 100>>, the call will be worthless, but the put will go into the money. It will take on the characteristics of a long underlying position, resulting in a loss of one point for each point the underlying price falls.

The position will break even if either the call or the put is worth 7.75. This will happen if the underlying price is at 107.75 (the call is worth 7.75) or at 92.25 (the put is worth 7.75). Above 107.75 or below 92.25, the potential loss to the position is unlimited.

Instead of selling a call and put at the same exercise prices, one might instead sell a call and a put at different exercise prices. For example, a trader might sell a May 95 put for 1.50 and sell a May 105 call for 2.40. The expiration profit and loss diagram looks as follows:

If the underlying contract is between 95 and 105 at May expiration, the May 105 call and the May 95 put will be worthless, and the trader will get to keep the total premium of 3.90.

If the underlying contract is above 105>>, the put will be worthless, but the call will go into-the-money. It will take on the characteristics of a short underlying position, resulting in a loss of one point for each point the underlying price rises.

If the underlying contract is below 95>>, the call will be worthless, but the put will go into-the-money. It will take on the characteristics of a long underlying position, resulting in a loss of one point for each point the underlying price falls.

The position will break even if either the call or the put is worth 3.90. This will happen if the underlying price is at 108.90 (the 105 call is worth 3.90) or at 91.10 (the 95 put is worth 3.90). Above 108.90 or below 91.10, the potential risk to the position is unlimited.

In both examples, the trader’s potential profit is limited to the premium received, while the potential risk is unlimited in either direction.

Buying a Call and Selling a Call

Consider the position where a trader buys a May 95 call for $7.65 and sells a May 105 call for $2.40. If the stock is at or below $95 at May expiration, both the 95 call and the 105 call will be worthless, so the trader will lose $5.25 (the $7.65 they paid for the May 95 call, less the $2.40 they received for the May 105 call).

With the stock at or above $105, both options will be in-the-money, and the May 95 call will be worth exactly 10 points more than the May 105 call. The resulting profit will be 10 points less the initial debit of $5.25, or $4.75. The expiration profit and loss diagram looks as follows:

Buying a Put and Selling a Put

Consider the position where a trader buys a May 100 put for 3.25 and sells a May 110 put for 10.30. With the underlying price at or above 110 at May expiration, both the 100 put and the 110 put will be worthless, and the trader will get to keep the total premium of 7.05 (the 10.30 received for the May 110 put, less the 3.25 paid for the May 100 put).

With the underlying price at or below 100, both options will be in-the-money, and the May 110 put will be worth exactly 10 points more than the May 100 put. The resulting loss will be 10 points minus the initial credit of 7.05, or 2.95. Between 100 and 110, the result will be between a loss of 2.95 and a profit of 7.05. The expiration profit and loss diagram looks as follows:

What would happen if a trader were to take the opposite position, selling a May 100 put for 3.25 and buying a May 110 put for 10.30? With the underlying price at or above 110 at May expiration, both the 100 put and the 110 put will be worthless, and the trader will lose their investment of 7.05 (the 10.30 paid for the May 110 put, less the 3.25 received for the May 100 put).

With the underlying price at or below 100, both options will be in-the-money, and the May 110 put will be worth exactly 10 points more than the May 100 put. The resulting profit will be 10 points minus the initial debit of 7.05, or 2.95. Between 100 and 110, the result will be between a profit of 2.95 and a loss of 7.05. The expiration profit and loss diagram looks as follows:

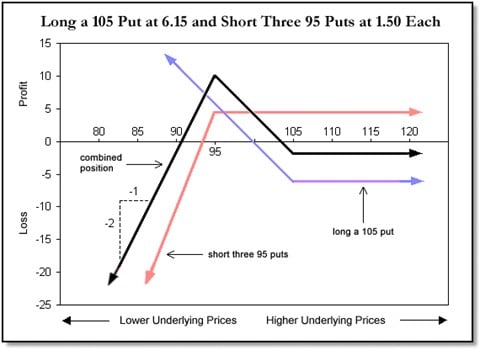

Buying and Selling Unequal Numbers of Contracts

Consider a position where a trader buys a May 105 put for 6.15 and sells 3 May 95 puts for 1.50 each. With the stock at or above 105 at May expiration, the May 105 put and the May 95 puts will be worthless, and the position will realize a loss of 1.65 (the 6.15 paid for the May 105 put, less the 4.50 received for the May 95 puts).

With the stock exactly at 95 at expiration, the May 105 put will be worth 10, while the May 95 puts will be worthless. The resulting profit will be the 10-point value of the position less the initial debit of 1.65, or 8.35. With the stock below 5, the May 105 and the May 95 puts will go into-the-money, taking on the characteristics of a short stock position.

Since the trader is short one underlying contract, in the form of a long May 105 put, and long three underlying contracts, in the form of three short May 95 puts, their net position is long two underlying contracts. For each point that the underlying stock falls below 95, the position will lose 2 points. The expiration profit and loss diagram looks as follows:

Risk-Reward Characteristics of Combination Strategies

The limited or unlimited risk/reward characteristics of combination positions are consistent with those of individual option positions:

| Position | Upside Risk-Reward | Downside Risk-Reward |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Chapter 08

Hedging Strategies

Options Hedging Strategies: Protective, Covered, Combination

If you're venturing into the world of investments or seeking to fortify your existing portfolio, understanding the art of hedging with options strategies can be your key to financial safety and successful downside protection. In this guide, we'll immerse ourselves in the basics of options hedging strategies, equipping you with the knowledge and techniques to safeguard your investments and navigate the often-turbulent waters of the financial markets.

What is Options Hedging?

Let's start with the basics. What exactly is options hedging, and why is it crucial? The financial markets are unpredictable, with constant fluctuations in the prices of stocks, commodities, and currencies.

This can be attributed to various factors such as economic data, geopolitical events, and market sentiment. These fluctuations can present both opportunities and risks. Although they offer the chance for significant gains, they also expose investors to significant potential losses.

Options hedging is a risk management strategy that can offset potential losses in an underlying asset. This involves using options contracts to protect portfolios from adverse market movements while enabling investors to participate in potential upside gains.

Why Options Hedging Matters

Hedging options is similar to buying insurance for your investments. Just like you insure your car or house to shield yourself from unforeseen disasters, hedging options is a way to protect your wealth against unexpected financial turbulence. This is why it's essential to consider options hedging.

- Risk Mitigation: One strategy to limit potential losses and minimize the impact of adverse market movements on your portfolio is options hedging. This is especially important during economic downturns or periods of increased volatility.

- Portfolio Diversification: You can customize hedging strategies to suit your portfolio, offering an extra level of diversification beyond the typical asset allocation.

- Preserving Capital: One way to safeguard your capital is by hedging, which guarantees you have enough resources to take advantage of opportunities once the market stabilizes or shifts.

Options are often used as a hedge against a position in the underlying instrument. Of course, all hedging strategies, including those involving options, entail a cost: What is one willing to give up under some favorable market condition to protect oneself against some adverse market condition?

This cost may come as an outright payment – for example, the premium one must pay to purchase an option. Or the cost may come in the form of some lost opportunity – for example, a limited profit when the market moves favorably.

Finally, the cost may come in the form of an additional risk – perhaps the strategy will reduce the risk resulting from one set of market conditions but will, at the same time, increase the risk resulting from a different set of conditions. One must first understand the basic hedging strategies to decide whether the cost is worthwhile.

Protective Options

Suppose a trader has a long position in the underlying contract. The trader hopes for an upward move in the underlying contract but worries about a downward move. One way to hedge the position against a downward move is to purchase a protective put. The profit and loss profile for such a position at expiration is shown below.

Note that the position is protected on the downside since the trader can exercise the put if the underlying contract falls below the exercise price.

At the same time, the position still has unlimited upside profit potential. If the underlying market should rise above the exercise price, the trader can let the put expire unexercised. The cost of executing the strategy is the loss of the premium paid for the put.

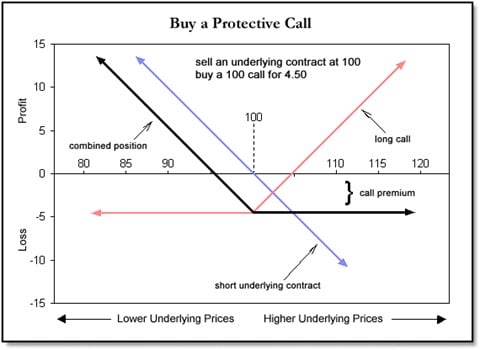

In the same way, suppose a trader has a short position in the underlying contract. Now, the trader hopes for a downward move in the underlying contract but is worried about an upward move. The trader might purchase a protective call to hedge the position against an upward move. The profit and loss profile for this position at expiration is shown below.

The position is protected on the upside since the trader can exercise the call if the underlying contract should rise above the exercise price. At the same time, the position still has unlimited downside profit potential. If the underlying market should fall below the exercise price, the trader can simply let the call expire unexercised. The cost of executing the strategy is the loss of the premium paid for the call.

Which protective option should a trader purchase? The answer depends on the amount of protection being sought and the amount of premium one is willing to pay. Far out-of-the-money options cost less, but they also afford less protection. Deeply in-the-money options cost more, but they afford greater protection.

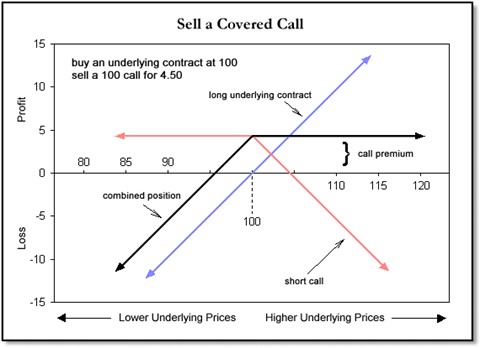

Covered Options

Instead of hedging a position in the underlying contract by purchasing a protective option, a trader might decide to sell a covered option. For example, a trader with a long underlying position might sell a covered call. The profit and loss profile for such a position at expiration is shown below.

While a covered call and a protective put can hedge a long underlying position, the two strategies have significantly different characteristics. Unlike a protective put, a covered call still has unlimited downside risk; the position is protected on the downside only to the extent of the premium received for the call. If the underlying price falls more than this premium, the covered call ceases to act as a hedge.

At the same time, a covered call has limited upside profit potential. The trader will be assigned on the call if the underlying price exceeds the exercise price at expiration. Their potential profit is limited to the difference between the original underlying price and the exercise price, plus the premium received for the call.

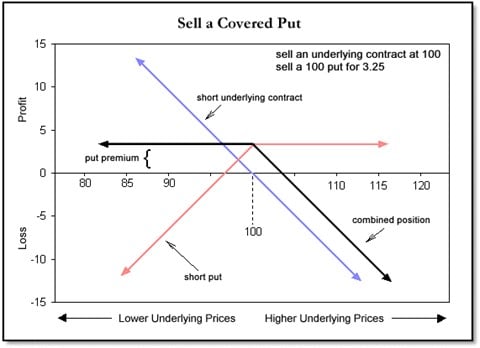

In the same way, instead of buying a protective call, a trader with a short underlying position might sell a covered put. The profit and loss profile for such a position at expiration is shown below.

Unlike a protective call, a covered put still has unlimited upside risk; the position is protected on the upside only to the extent of the premium received for the put. If the underlying price rises more than this premium, the covered put ceases to act as a hedge. At the same time, a covered put has limited downside profit potential.

The trader will be assigned to the put if the underlying price is below the exercise price at expiration. Their potential profit is limited to the difference between the original underlying price and the exercise price, plus the premium received for the put.

When the underlying is bought, and a covered call is simultaneously sold as a hedge against the position, the strategy is sometimes referred to as a buy/write (buy the underlying, write the option).

As a hedge, the sale of a covered option is significantly inferior to the purchase of a protective option. The latter offers limited risk and unlimited reward. Still, if option prices are high, a hedger may not be willing to pay the premium required for a protective option. In such a case, they may decide that selling a covered option at a high price, even with its limited protection and reward, represents a sensible hedging strategy.

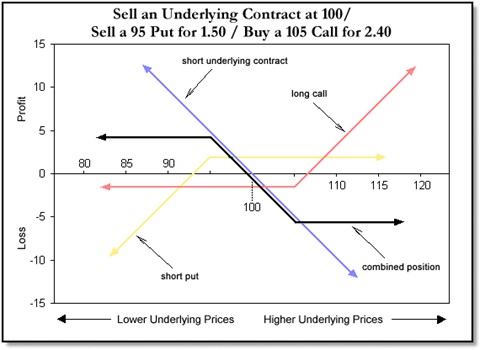

Combination Hedges

A trader can also combine the purchase of a protective option with the sale of a covered option. For example, a trader with a long underlying position might simultaneously buy a protective put and sell a covered call. The profit and loss profile for such a position at expiration is shown below.

As with a protective put, the position has limited downside risk.

If the underlying contract falls below the put’s exercise price, the trader can exercise the put. As with a covered call, the position has limited upside profit potential. If the underlying contract rises above the call’s exercise price, the trader will be assigned on the call.

In the same way, a trader with a short underlying position might simultaneously buy a protective call and sell a covered put. The profit and loss profile for such a position at expiration is shown below.

As with a protective call, the position has limited upside risk. If the underlying contract rises above the call’s exercise price, the trader can exercise the call. As with a covered put, the position has limited downside profit potential. If the underlying contract falls below the put’s exercise price, the trader will be assigned on the put.

Hedgers refer to the combination strategy of buying a protective option and selling a covered option using various terms, including fence, collar, or range forward. A long fence or collar is a hedge with a long underlying position. When the hedge includes a short underlying position, it is a short fence or collar.

The strategy is popular because the premium received from the sale of the covered option will somewhat offset the premium paid for the protective option. When the premium for both options is the same, the strategy becomes a zero-cost collar.

Chapter 09

Types of Orders

Options Order Types: The Basics

Clients can submit orders to buy or sell contracts on an exchange in multiple ways, depending on their preferences. To fully utilize the potential benefits of options, it is crucial to understand how different order types work.

Additionally, under some conditions, the exchange may impose restrictions on trading. This may prevent an order from being executed by the trader's desires. A trader should be familiar with these restrictions to avoid unexpected and potentially heightened risks.

Market Orders

The most common type of order is a market order.

A market order is an order to be executed at the best price when the order reaches the exchange. When you place a market order to buy an ABC March 100 call, it will be executed at the best offer price for ABC March 100 calls at the time the order reaches the exchange. A market order to sell an XYZ September 65 put will be executed at the best bid price for XYZ September 65 puts at the time the order reaches the exchange.

Regardless of the number of contracts in the order, a market order must be filled in its entirety. This may mean that not all contracts are executed at the same price. If there are five ABC March 100 calls offered at 2.75 and five ABC March 100 calls offered at 3.00, a market order to buy ten ABC March 100 calls will result in purchasing five calls at 2.75 and five calls at 3.00.

A market order is used when a trader wants to execute the order as quickly as possible. Even so, a trader should know the price at which a market order will be executed. Otherwise, the trader may be surprised that they bought or sold contracts at a price significantly different than expected.

Limit Orders

If a trader is more concerned with the price at which an order is executed than the speed at which it is executed, they can place a limit order. A limit order is an order to be executed at a specific price. When a limit order reaches the exchange but cannot be executed at the specified price, the order remains in the order book until it can be executed.

For example, a limit order to buy an ABC March 100 call at 2.50 can only be executed if an offer is to sell ABC March 100 calls at 2.50 or better.

Of course, there is nothing to prevent a limit order from being executed at a better price than the limit price whenever possible. A limit order to sell an XYZ September 65 put at 4.25 can only be executed if the bid price for XYZ September 65 puts is 4.25 or higher. However, if the best bid price when the order reaches the exchange is 4.35, the order will be filled immediately at the better price of 4.35.

Depending on market conditions, a limit order may only result in a partial execution. Suppose an order is submitted to purchase ten September 65 calls with a limit of 4.25. In that case, the exchange will execute as many of the ten contracts as possible at the limit price or better and hold the remainder of the order until the bid price returns to 4.25. The trader may find that they have sold two contracts at 4.35, five at 4.25, and three contracts were not executed.

Stop Orders

Sometimes, a trader will want to submit an order contingent upon the price a contract has traded during the day. Such an order is known as a stop order.

For example, a trader may submit a market order to buy five ABC March 100 calls at 2.50, but only if the underlying contract trades at 105.00 or higher. If the underlying contract never trades at 105.00 or higher, the order to buy ABC March 100 calls will never be executed.

If the underlying contract trades at 105.00 or higher, the order to buy five ABC March 100 calls becomes a market order and will be executed at the best offer price when the underlying contract reaches 105.00.

A stop can also trigger a limit order. A trader might submit a limit order to sell ten XYZ September 65 puts at 4.50 if the underlying contract trades at 68.00 or higher. If the underlying contract never trades at 68.00 or higher, the order to sell XYZ September 65 puts will never be executed.

If the underlying contract trades at 68.00 or higher, the order to sell ten September 65 puts at 4.50 becomes a limit order. If there is a bid of 4.50 or higher when the underlying contract reaches 68.00, the order will be executed immediately. Otherwise, the exchange will hold the order until there is a bid of 4.50 for the XYZ September 65 puts.

Stop orders are usually placed to limit the losses when a market moves adversely to a trader’s position.

Time In Force

Traders can also define additional instructions for how long the want their order to remain in the order book by setting a specific Time In Force or TIF for each order. Here are some of the most common TIFs.

Day Order (DAY) – The order will remain in the order book until it is filled or until the end of the trading session. The exchange will automatically cancel the order at the end of the trading session.

Good-Till-Cancel (GTC) - The order will remain in the order book until they are completely filled or the instrument expires.

Immediate-Or-Cancel (IOC) –If an order needs to be executed immediately, it is called an Immediate or Cancel (IOC) order. If the order cannot be fulfilled immediately, it will be canceled automatically. However, there may be a chance for a partial execution depending on the market prices at the time of the order placement.

Example: A exchange receives an order to buy 25 ABC March 100 calls for 2.50, immediate or cancel. If the best offer in the order book for March 100 calls is 2.50, but the offer is for 15 contracts only, the exchange will fill 15 of the March 100 calls and cancel the order for the remaining 10 March 100 calls.

Fill-Or-Kill (FOK) – An order that must be executed immediately and completely. Failing this, the order is automatically canceled. An FOK order must be completed in its entirety.

Example: A exchange receives an order to buy 25 ABC March 100 calls for 2.50, fill-or-kill. If the best offer in the marketplace for March 100 calls is 2.50, but the offer is for 15 contracts only, the exchange cannot immediately fill the order so the order is automatically canceled.

Market-On-Close (MOC) - An order may also be designated as market-on-close (MOC). Regardless of other contingencies (such as a price limit), an MOC order becomes a market order at the trading day's close.

Trading Restrictions

Many option strategies involve trades in both options and the underlying contract. Due to exchange or government regulations, it may only sometimes be possible to trade either the underlying contract or options, even during regular exchange trading hours.

There may also be restrictions on trading the underlying stock or futures contract due to trading halts. This can happen when a futures contract reaches a specified price limit (up or down) during the day’s trading. When this happens, the futures market is said to be locked, and trading can only resume that day if the market retreats from the specified limit price. In some futures markets, a halt in futures trading may not result in a suspension of trading on the associated options.

Often, the same price limit that triggers a locked futures market is the same one that triggers a locked option market. Options prices, however, tend to change more slowly than the underlying futures price. This means that the options may still be trading because they have not yet reached the price limit, even though the underlying futures market is already locked.

A stock exchange may also impose a temporary trading halt when a specified stock index has a sufficiently large downward move. Depending on the severity of the action, the market may or may not open again for trading on the same day. When trading in the underlying stock is halted, trading in the associated options is usually halted simultaneously.

Every trader should check with the appropriate exchange to become familiar with any trading restrictions affecting their strategies.